It’s finally over. I survived a year as a School Direct (Salaried) trainee. I made it to the end, I qualified, and I have a job as a Newly-Qualified Teacher (NQT) next year. This is nothing short of a miracle, but it was the children and some amazing colleagues who made it possible. (If you want quick School Direct tips or a ‘should I / shouldn’t I?’ guide, skip to ‘Cut to the chase’ at the end of this post).

School Direct replaced the Graduate Teacher Programme (GTP) last year, and I was among the thousands of guinea-pigs nationwide on the new scheme. It was a learning experience not just for us students, but also for schools and the universities.

The GTP was the standard year-long on-the-job route into teaching for someone with a degree who worked as a Teaching Assistat (TA). School Direct is different because instead of applying to a university and then finding a school placement, the you applied to the school. The school is in charge.

The other difference, or so I believed, was that School Direct was aimed at people like me: career changers. This was certainly the spin coming from the Department for Education (DfE). It seemed Michael Gove wanted ex-squaddies or mardy middle-aged grammar school-educated blokes with O-Level Latin and A-Level Computer Science as primary teachers, and I certainly fitted one of those categories perfectly.

Working for the BBC for 22 years, I’d never worked as a TA, and I only had 2 weeks’ experience in a primary school. I inhabited another world. This is what I was doing almost exactly a year ago:

When I started applying for the (hugely competitive) Salaried School Direct, however, I realised that as a career-changer, I was the exception. I spent a day in one school doing round after round of X-Factor style auditions, where I was the oldest person by far (45 at the time). I only met one other career-changer that day, a young police officer. He was outstanding, and I was thrilled when he got a place. An open day at another school left me with the distinct impression that as far as some schools were concerned, School Direct was no different from the GTP, and no-one with little experience of working with children would make the cut.

Somehow, I did. And when I started, I found I was only one of two career-changers in four schools, and even at college we were the exception; we sought each other out, we could sense the desperation in each other’s eyes. I met a tree surgeon. And a tax lawyer. Or was it a tax lawyer who packed it in to become a tree surgeon and then tried teaching? But almost everyone on the scheme had worked as a TA, some for many years. They spoke a different language: not just the jargon that goes with any profession, but they had a familiarity with the daily business of school life and learning that was utterly alien to me, as an outsider.

Time expands

I spent my first school week in a state of shock. Culture shock. According to Wikipedia, culture shock, has the following features: ‘information overload, language barrier, generation gap, technology gap, skill interdependence, homesickness.’

It’s fair to say I experienced all of those at different times.

Time expanded; I’d moved from an environment in BBC radio where perhaps 3 or 4 noteworthy things might happen to me in a day, to one where the demands of 30 children meant that dozens of fascinating things were occurring around me all the time. My brain is still adjusting to coping with the amount of information I need to process in a day, and one result of this is that things that happened yesterday still feel like they happened a week ago.

Hat-juggling

I faced many challenges, but perhaps the greatest was, to mix metaphors, the juggling act required to know which hat I was wearing at any given time: teacher, student and teaching assistant; finding the time for everything I had to do for college as well as starting to plan and teach my own lessons, ensure that my class teacher felt supported and be a parent to three school age children. I never got the hang of that. I only survived the year by dropping one of the hats, usually the college work. I don’t think I read with my own daughter all year. The long hours in school, and long evening hours spent trying to study and plan lessons took a hideous toll on family life, the full extent of which only became fully apparent to me when I qualified and finally had a moment to look around me and notice what was going on at home.

Planning lessons took me an eternity; I probably spent 3 or 4 hours preparing each hour-long lesson. I think it’s hard for anyone who’s been teaching for any length of time to understand the sheer horror of being a trainee teacher, staring at a blank lesson proforma. It’s like extreme writers’ block. Qualified (and even newly-qualified) teachers will breezily say ‘oh find a nice activity or game’ and the student then spends a whole evening scouring the TES web site for things, none of which quite fit the learning intention you had in mind. It’s easier now, but it was only in the summer term I found I could plan a lesson in anything that was much faster than real time.

Putting CPD into practice

By the end of the Spring term, however, I was developing an increasing awareness of how children learn, through a combination of college lectures, practical experience and school Continuing Professional Development (CPD).

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs becomes tangible and meaningful when you are working each day with children who may have their most basic physiological needs met, but who may be lacking in feelings of love and belonging, and may be low in self-esteem. A CPD session on attachment theory, brought together some of John Bowlby’s original ideas with recent findings from neuroscience, and painted a compelling picture of how neglect can affect learning, behaviour and the physical development of the brain. I was able to see possible links between this and a child who, unexpectedly, started to seek attention through petty theft and vandalism. My training gave me a greater understanding of where this behaviour was coming from, so I could deal with the child more effectively and sensitively.

Finding my own voice

In my teaching, was starting to find my own style, and my own voice, experimenting with some more creative ideas of my own:

Second School Experience

My second school experience in Year 2 in a different school brought a new, milder form of culture shock. New colleagues, new children, a larger school, classrooms so much physically larger I almost had agoraphobia on my first day. I had to think carefully about where to position myself (and the children) so I could be heard.

As my teaching load increased I found work-life balance increasingly hard to manage. Fortunately I had the support of a fantastic class teacher. She saw me through tough times with her unquenchable optimism, Tigger to my Eeyore, working with me much as she would with children in her class, talking through my lesson plans in detail, making me realise for myself what would and wouldn’t work, and making my lessons better as a result. This helped me appreciate the benefit to children of learning this way, reaching your own conclusions rather than just being told the answer.

I learned so much from her, but the chief things were:

- Allowing time for responding to marking each day – marking only makes any sense if children have time to read and act on your comments. You can have a dialogue about learning with children this way.

- Knowing something about the children’s life and interests outside school – any interest can be a hook to engage them in learning.

- Bringing lessons full circle by reviewing in the plenary the learning that has been achieved.

My proudest achievement in my second school was teaching computer programming to children much younger than normally attempted, in a setting where there were about 3 laptops that worked. Normally Scratch is only taught – even by the experts – to upper KS2, but my experience of teaching it in Year 3 made me think that it was worth a go in Year 2.

The risk paid off. I used a combination of whole-class teaching with practical activities: children cut out instructions, arranged them on sugar paper, and then brought them to one of the few computers we had for testing. I was also able to use Scratch to make my own interactive resources for teaching maths that fitted in with our literacy topic on Scaredy Squirrel.

As in Year 3, the chief joy was finding the unexpected children who have a natural aptitude for programming: the boy who struggles with maths and literacy, but becomes the class expert at something for the first time in his life, helping and teaching others, raising his self-esteem; the girl who would shun computing if introduced to it later in life (for girls ‘year 8 is too late’), but who showed a natural aptitude for the logical thinking required to plan and write computer code. This is about broadening horizons, thinking ahead not just to KS2, but to secondary school and beyond, giving children more career choices.

As in Year 3, the chief joy was finding the unexpected children who have a natural aptitude for programming: the boy who struggles with maths and literacy, but becomes the class expert at something for the first time in his life, helping and teaching others, raising his self-esteem; the girl who would shun computing if introduced to it later in life (for girls ‘year 8 is too late’), but who showed a natural aptitude for the logical thinking required to plan and write computer code. This is about broadening horizons, thinking ahead not just to KS2, but to secondary school and beyond, giving children more career choices.

Whilst in my second school, I also ran a weekly debating club for Year 5; discussions with children in this age group on a range of controversial issues – the environment, mobile phones – helped me improve my understanding of how older children think and what motivates them. They can be very passionate about issues, but need to develop skills to organise their thoughts, and express their ideas more clearly. I found this very rewarding; I talked about my experience watching debates, like Prime Minister’s Questions, in the House of Commons. I’d like to build on this in my future career, teaching debating as a skill and also taking children to Parliament to find out more about how we are governed.

Wrong man for the course

It was at the end of (my rather wobbly) second school experience, my tutor told me ‘you should never have been accepted on the course.’ She’d said this once before, and I’d been a bit taken aback, but this time I knew what she meant. I had recently come very close to quitting for the second time, after a bad observation. I’d thought that if I was that bad, that far into the course, there really was no hope. I was physically and mentally exhausted, walking to school with tears in my eyes every morning, and getting ill. I was working about 10 times harder than I had done in the BBC (all day, every day, every evening until I was so tired I could no longer think, including weekends) and earning less than half the money. In my old job, I could switch off when the red light went out, but now my work followed me home, filling my every waking (and sleeping) moment. I just wanted to stop.

But, with the help of my class teacher, I turned things round and delivered that computing lesson (without computers) that just went swimmingly.

Also, I had been accepted on the course. I couldn’t help that. Well, I could not have applied, I suppose, but the reason I did was that I couldn’t afford to do a PGCE. If you look at the fees involved in a PGCE, and add that to the salary I got paid to do the School Direct (Salaried) route, you’re looking at a cost of about £27,000 for doing a PGCE. I had three children to feed and clothe. There was no other possible route for me into teaching.

Final term: eighty percent teaching load

Shortly before the start of the summer term I was asked ‘How do you feel about the 80% teaching load?’ A fair question, but I think I coped better than expected. Coming back to my base school felt like coming home. I got into a routine, speeding up the planning process by making better use of resources and the experience of colleagues.

Getting an NQT job on my first job interview was a pivotal moment. This provided me with an even greater focus and incentive: I really was now going to turn from being a radio studio manager into a primary school teacher.

Gardner’s World

Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences includes, alongside linguistic, musical, logical, spatial, kinesthetic and so on, one that is often overlooked: naturalist intelligence – this is to do with having an affinity with the natural world, living things and ecosystems.

I first came across this when doing some reading on behaviour management early on in the year, but it only really made sense when I experienced it first hand when working on planting fruit and vegetables with a group of ‘difficult’ children. They impressed me with their hard work, and the great care they took handling living things; one child in particular, whose behaviour could be very challenging, was a joy to work with. Handling the plants, the child was focused, well-behaved and enjoying the learning. Food for thought: this could be another way of improving self-esteem and outcomes for some hard-to-reach children.

Riffing

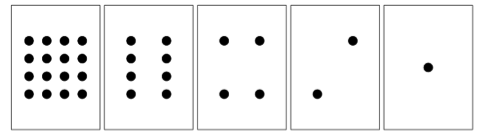

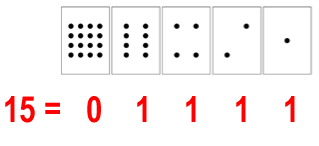

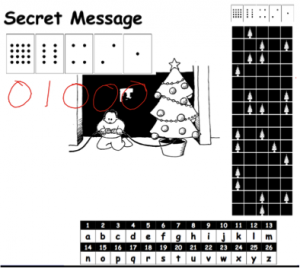

I finally got an inkling that I might be good at this when half my class went out on a sports tournament. Alone, no teacher, no TA, I had a whole morning to fill. I got a sense of the possible joys of teaching by bringing my knowledge and experience into a cross-curricular morning of history, maths, ICT and a dash of PSHE. I used the 70th anniversary of D-Day (the ‘longest day’) to take the children on a virtual journey to the Normandy beaches, thinking about the importance of secrecy, code-breaking, Bletchley Park, computers and how they store information as binary numbers. We did binary maths, we broke and made codes. Some children accused others of cheating, so we talked about espionage and what’s fair in war (if not love). I had taken a theme and riffed on it, and the children loved it. It remains my favourite moment of the year (closely followed by getting the children to make musical instruments with a MakeyMakey in a combined DT / music / ICT lesson).

Apart from that, did you enjoy the play?

Here are a couple of observations I’ve made that have resonated with other teachers:

First:

‘My best AND worst lessons are planned on the hoof, or at very short notice.’

My next challenge is to work out how to make all my lessons fall into the former category. I suspect this will take the rest of my teaching career, through a process of continuing reflection and learning, striving to improve my subject knowledge and pedagogy.

Second:

‘A key quality for being a teacher is deriving pleasure from other people’s achievements.’

I’m hugely passionate about this idea; for me, it’s the fundamental reason why I became a teacher. It came back to me when I was watching the end of year music concert. I got more pleasure out of watching children, some whom I’d taught, some I barely knew, on stage and doing their best than I got out of any number bands on Later With Jools Holland. I probably looked like a fool with a huge grin on my face, but it was sincere. I may be naive, but I can’t understand adults who sit stony-faced at such occasions.

I am more rewarded every single day as a teacher, even on the bad days, than I was in 22 years working for the BBC. Key to that is the constant desire to want the best for the children, to give them the tools to progress, to open up as many options as possible for them in later life, and to ensure that in my classroom they are happy.

Cut to the chase…

Would I recommend the School Direct route to anyone? Well, I have to say, if you have young children: no. A friend told me that on her GTP course, half the students’ relationships broke up in their training year. I’m not surprised. Unless your partner is Wonder Woman or Superman, the price your family will pay may well not be worth it. For anyone else: yes, but a few things to consider:

- Don’t use normal notebooks, write everything in spiral-bound hole-punched note pads with detachable pages – everything is evidence. You will need it for your standards folder. Sounds simple, but this was probably the best single piece of advice I was given, thankfully early on by my class teacher (herself a career changer).

- The schools are now in charge, so make sure you pick a good one. Larger schools may well offer more flexibility with things like PPA and observation time, but balance that against being known and being able to get to know every child and member of staff in a smaller school. Ask about additional adults. It’ll probably just be you and the teacher in class, but some schools have additional TAs and there may be Learning Support Assistants (LSAs). LSAs are there for a reason, but an extra adult can make a huge difference.

- Having said that, the academic institution matters too. On my course the college days were all over by January, varying between 1 and 2 days a week, but the quality of the teaching in college was hit and miss. When you have so few days in college, and you’re working with some people who spent four years learning about the theory of how children learn, those college days are so precious. It’s not a great feeling to be sitting in a lecture or tutorial thinking you are wasting your time when you have 90 books to mark and lessons to plan, though the opportunity to talk to fellow students in other schools is invaluable.

- Get your PPA time nailed down. In writing, if possible. It varies hugely between schools: some have fixed whole days with joint planning, in others you take it in chunks when you can. Clearly, fixed whole days are likely to be more productive.

- Your class teacher can make or break you. I was pretty darn lucky, but I’ve heard some horror stories about some class teachers (not in any school I taught in, I hasten to add) who do not support students, and, in some cases, actively undermine them. I don’t know why people like that become teachers, but I’ve heard enough stories at college to conclude they do exist. They need to find new careers, and school managements need to think very carefully about who makes a suitable mentor for a student, regardless of the student’s age or apparent experience.

- I think it’s fair to say that School Direct had its teething problems in its first year. The shift in ‘ownership’ from universities to schools left many confused as to who was in charge, and some things were neglected as each institution thought the other was dealing with it. Much of the paperwork was adapted (or not) from the GTP, and was insanely repetitive. It will be better next year. The bane of my life was the training record. I had to account for every hour of training given in school and college, though I couldn’t work out why this was my resposibility, in an unworkable Word document. Next year, at least one college is folding this into the weekly reflective journal, so there’s no end-of-term panic to fill it in.

- You will find your role confusing. You may find that you are a TA when it suits, a teacher when it suits – meaning you may need to sharpen the pencils, do playground duties AND take sole responsibility for the class. I would sigh as PGCE students left at 4.30 pm (though I’m not saying the PGCE is an easier route – I had far, far less academic work). If you’re on the Salaried School Direct scheme, you do have to remember that you’re being paid to do a job.

This is an expanded version of a presentation I gave as part of my final assessment, and in a staff meeting to colleagues.

NB: Since writing this post I have moved to secondary teaching – please read comments below – my views may have changed since writing this article!